「以 Kotlin 開發 Android 應用程式」課程假設您已熟悉多執行緒的概念和術語。這個頁面屬於概略介紹和複習性質。

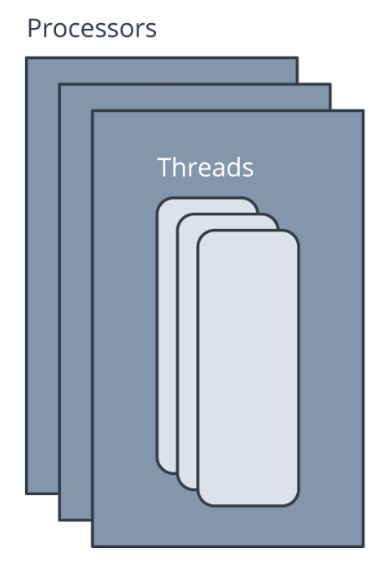

行動裝置都有處理器,而現今的裝置多半都有多個硬體處理器,各處理器會同時執行處理程序。這就是所謂的「多重處理程序」。

為了更有效率地使用處理器,作業系統可讓應用程式在處理程序內建立多個執行緒。這就是「多執行緒」功能。

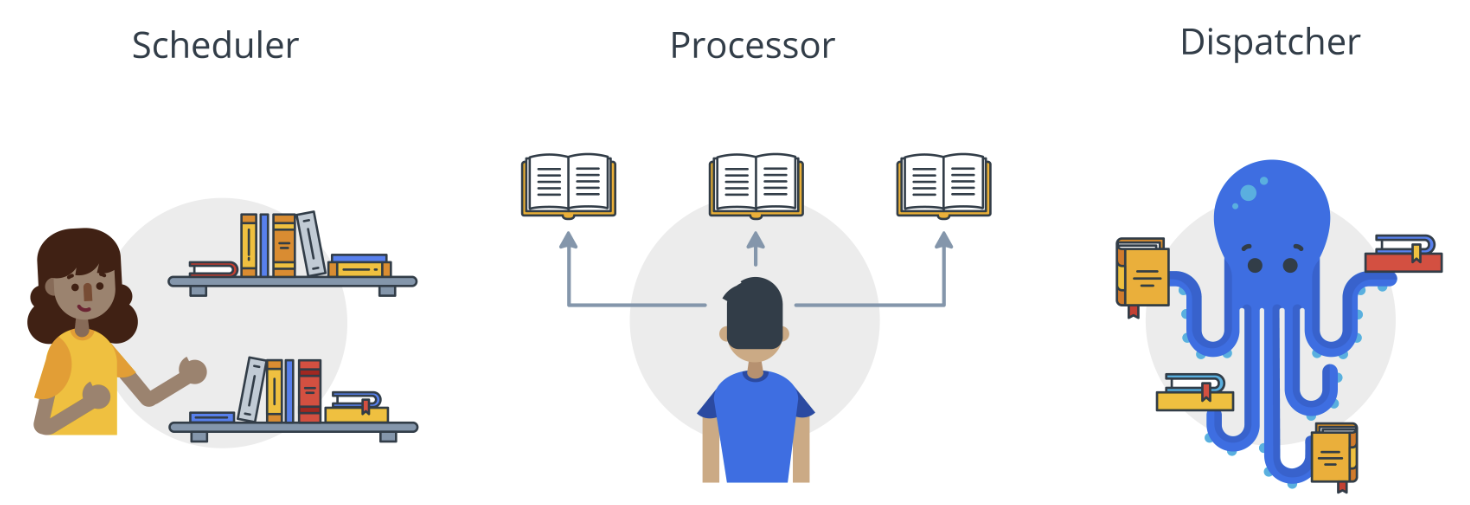

這就像是同時閱讀多本書籍、每讀一章就換另一本,最終可以讀完所有書籍,但是同一時間點只能閱讀一本書。

要管理所有執行緒,需要略為動用基礎架構。

「排程器」會將優先順序等因素納入考量,確保所有執行緒都能順利完成執行。任何一本書都不該永遠在書架上積灰塵,但是如果書籍篇幅很長或者可以稍後再讀,可能要一段時間後才會送到您手中。

「調度工具」會設定執行緒,負責傳送您需要閱讀的書籍,並指定相關作業的結構定義。您可以將結構定義視為獨立的特殊閱讀室。某些結構定義最適合使用者介面作業,有些則專門用於處理輸入/輸出作業。

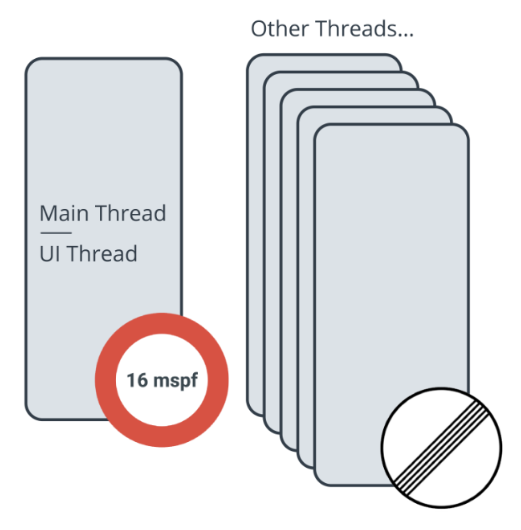

唯一需要另外注意的是,使用者導向的應用程式通常會具備在前景執行的「主執行緒」,並且會調度可在背景執行的其他執行緒。

在 Android 中,主執行緒是處理所有 UI 更新的單一執行緒,又稱為「UI 執行緒」,這個執行緒同時也會呼叫所有點擊處理常式,以及其他 UI 和生命週期回呼。UI 執行緒是預設執行緒。除非應用程式明確切換執行緒,或是使用在其他執行緒上執行的類別,否則應用程式只會在主執行緒上進行各項工作。

這可能是個挑戰。UI 執行緒必須順暢執行,才能確保提供優質的使用者體驗。為了避免使用者在應用程式中遇到任何卡頓情形,主執行緒每 16 毫秒或更短的間隔 (大約每秒 60 影格數) 就必須更新畫面一次。就這個速度來看,人類眼中的影格變動過程完全可說是行雲流水。但要達到此效果,需於短時間內處理大量影格。因此在 Android 上,如何避免 UI 執行緒遭到封鎖,就顯得相當重要。「封鎖」在此情境下是指,UI 執行緒在等待其他事項 (例如等待資料庫完成更新) 期間,完全未執行任何動作。

許多常見工作耗時超過 16 毫秒,例如從網際網路擷取資料、讀取大型檔案,或是將資料寫入資料庫。因此,如果從主執行緒呼叫程式碼來執行這類工作,可能會導致應用程式暫停、延遲,乃至凍結。但是,如果封鎖主執行緒的時間過長,應用程式甚至可能會當機,並顯示「應用程式無回應」(ANR) 對話方塊。

回呼

您可以透過幾種不同的方式處理主執行緒上的工作。

在不封鎖主執行緒的情況下,有種執行長時間工作的模式稱做「回呼」。利用回呼,您可以開始在背景執行緒上長時間執行工作。工作完成後,系統會呼叫做為引數的回呼,然後將結果告知主執行緒上的程式碼。

回呼算是不錯的模式,但有些缺點。大量使用回呼的程式碼會變得不易讀取且難以推論,因為程式碼雖然看起來是依序執行,但回呼程式碼日後會在某些非同步的時間點執行。此外,回呼也不允許使用例外狀況等部分語言功能。

協同程式

在 Kotlin 中,「協同程式」是能夠流暢有效處理長時間執行工作的解決方案。運用 Kotlin 協同程式,您可將以回呼為基礎的程式碼轉換為循序程式碼。依序編寫的程式碼通常較容易閱讀,甚至能使用例外狀況等語言功能。說到底,協同程式和回呼所做的工作其實並無二致,亦即等到長時間執行的工作產生結果,再繼續執行。