Android 4.4 (API level 19) introduces the Storage Access Framework (SAF). The SAF lets users browse and open documents, images, and other files across all of their preferred document storage providers. A standard, easy-to-use UI lets users browse files and access recent files in a consistent way across apps and providers.

Cloud or local storage services can participate in this ecosystem by implementing a

DocumentsProvider that encapsulates their services. Client

apps that need access to a provider's documents can integrate with the SAF with a few

lines of code.

The SAF includes the following:

- Document provider: a content provider that lets a

storage service, such as Google Drive, reveal the files it manages. A document provider is

implemented as a subclass of the

DocumentsProviderclass. The document-provider schema is based on a traditional file hierarchy, though how your document provider physically stores data is up to you. The Android platform includes several built-in document providers, such as Downloads, Images, and Videos. - Client app: a custom app that invokes the

ACTION_CREATE_DOCUMENT,ACTION_OPEN_DOCUMENT, andACTION_OPEN_DOCUMENT_TREEintent actions and receives the files returned by document providers. - Picker: a system UI that lets users access documents from all document providers that satisfy the client app's search criteria.

SAF offers the following features:

- Lets users browse content from all document providers, not just a single app.

- Makes it possible for your app to have long-term, persistent access to documents owned by a document provider. Through this access, users can add, edit, save, and delete files on the provider.

- Supports multiple user accounts and transient roots such as USB storage providers, which only appear if the drive is plugged in.

Overview

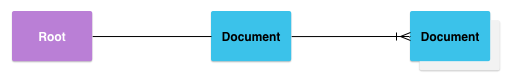

The SAF centers around a content provider that is a

subclass of the DocumentsProvider class. Within a document provider, data is

structured as a traditional file hierarchy:

Note the following:

- Each document provider reports one or more

roots, which are starting points into exploring a tree of documents.

Each root has a unique

COLUMN_ROOT_ID, and it points to a document (a directory) representing the contents under that root. Roots are dynamic by design to support use cases like multiple accounts, transient USB storage devices, or user login and logout. - Under each root is a single document. That document points to 1 to N documents, each of which in turn can point to 1 to N documents.

- Each storage backend surfaces

individual files and directories by referencing them with a unique

COLUMN_DOCUMENT_ID. Document IDs are unique and don't change once issued, since they are used for persistent URI grants across device reboots. - Documents can be either an openable file, with a specific MIME type, or a

directory containing additional documents, with the

MIME_TYPE_DIRMIME type. - Each document can have different capabilities, as described by

COLUMN_FLAGS. For example,FLAG_SUPPORTS_WRITE,FLAG_SUPPORTS_DELETE, andFLAG_SUPPORTS_THUMBNAIL. The sameCOLUMN_DOCUMENT_IDcan be included in multiple directories.

Control flow

The document provider data model is based on a traditional

file hierarchy. However, you can physically store your data however you like, as

long as you can access it using the DocumentsProvider

API. For example, you can use tag-based cloud storage for your data.

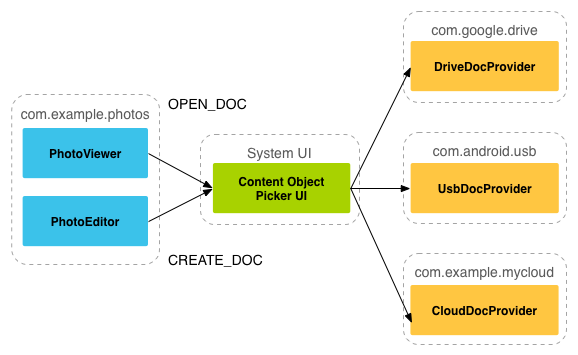

Figure 2 shows how a photo app might use the SAF to access stored data:

Note the following:

- In the SAF, providers and clients don't interact directly. A client requests permission to interact with files, meaning to read, edit, create, or delete files.

- The interaction starts when an application, in this example a photo app, fires the intent

ACTION_OPEN_DOCUMENTorACTION_CREATE_DOCUMENT. The intent can include filters to further refine the criteria, such as "give me all openable files that have the 'image' MIME type." - Once the intent fires, the system picker goes to each registered provider and shows the user the matching content roots.

- The picker gives users a standard interface for accessing documents, even when the underlying document providers are very different. For example, figure 2 shows a Google Drive provider, a USB provider, and a cloud provider.

In Figure 3, the user is selecting the Downloads folder from a picker opened in a search for images. The picker also shows all of the roots available to the client app.

After the user selects the Downloads folder, the images are displayed. Figure 4 shows the result of this process. The user can now interact with the images in the ways that the provider and client app support.

Write a client app

On Android 4.3 and lower, if you want your app to retrieve a file from another

app, it must invoke an intent such as ACTION_PICK

or ACTION_GET_CONTENT. The user then selects

a single app from which to pick a file. The selected app must provide a user

interface for the user to browse and pick from the available files.

On Android 4.4 (API level 19) and higher, you have the additional option of using the

ACTION_OPEN_DOCUMENT intent,

which displays a system-controlled picker UI that lets the user

browse all files that other apps have made available. From this single UI, the

user can pick a file from any of the supported apps.

On Android 5.0 (API level 21) and higher, you can also use the

ACTION_OPEN_DOCUMENT_TREE

intent, which lets the user choose a directory for a client app to

access.

Note: ACTION_OPEN_DOCUMENT isn't a replacement for ACTION_GET_CONTENT.

The one you use depends on the needs of your app:

- Use

ACTION_GET_CONTENTif you want your app to read or import data. With this approach, the app imports a copy of the data, such as an image file. - Use

ACTION_OPEN_DOCUMENTif you want your app to have long-term, persistent access to documents owned by a document provider. An example is a photo-editing app that lets users edit images stored in a document provider.

For more information about how to support browsing for files and directories using the system picker UI, see the guide about accessing documents and other files.

Additional resources

For more information about document providers, take advantage of the following resources:

Samples

Videos

- DevBytes: Android 4.4 Storage Access Framework: Provider

- Virtual Files in the Storage Access Framework