1. Before you begin

This codelab introduces you to concurrency, which is a critical skill for Android developers to understand in order to deliver a great user experience. Concurrency involves performing multiple tasks in your app at the same time. For example, your app can get data from a web server or save user data on the device, while responding to user input events and updating the UI accordingly.

To do work concurrently in your app, you will be using Kotlin coroutines. Coroutines allow the execution of a block of code to be suspended and then resumed later, so that other work can be done in the meantime. Coroutines make it easier to write asynchronous code, which means one task doesn't need to finish completely before starting the next task, enabling multiple tasks to run concurrently.

This codelab walks you through some basic examples in the Kotlin Playground, where you get hands-on practice with coroutines to become more comfortable with asynchronous programming.

Prerequisites

- Able to create a basic Kotlin program with a

main()function - Knowledge of Kotlin language basics, including functions and lambdas

What you'll build

- Short Kotlin program to learn and experiment with the basics of coroutines

What you'll learn

- How Kotlin coroutines can simplify asynchronous programming

- The purpose of structured concurrency and why it matters

What you'll need

- Internet access to use Kotlin Playground

2. Synchronous code

Simple Program

In synchronous code, only one conceptual task is in progress at a time. You can think of it as a sequential linear path. One task must finish completely before the next one is started. Below is an example of synchronous code.

- Open up Kotlin Playground.

- Replace the code with the following code for a program that shows a weather forecast of sunny weather. In the

main()function, first we print out the text:Weather forecast. Then we print out:Sunny.

fun main() {

println("Weather forecast")

println("Sunny")

}

- Run the code. The output from running the above code should be:

Weather forecast Sunny

println() is a synchronous call because the task of printing the text to the output is completed before execution can move to the next line of code. Because each function call in main() is synchronous, the entire main() function is synchronous. Whether a function is synchronous or asynchronous is determined by the parts that it's composed of.

A synchronous function returns only when its task is fully complete. So after the last print statement in main() is executed, all work is done. The main() function returns and the program ends.

Add a delay

Now let's pretend that getting the weather forecast of sunny weather requires a network request to a remote web server. Simulate the network request by adding a delay in the code before printing that the weather forecast is sunny.

- First, add

import kotlinx.coroutines.*at the top of your code before themain()function. This imports functions you will be using from the Kotlin coroutines library. - Modify your code to add a call to

delay(1000), which delays execution of the remainder of themain()function by1000milliseconds, or 1 second. Insert thisdelay()call before the print statement forSunny.

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

println("Weather forecast")

delay(1000)

println("Sunny")

}

delay() is actually a special suspending function provided by the Kotlin coroutines library. Execution of the main() function will suspend (or pause) at this point, and then resume once the specified duration of the delay is over (one second in this case).

If you try to run your program at this point, there will be a compile error: Suspend function 'delay' should be called only from a coroutine or another suspend function.

For the purposes of learning coroutines within the Kotlin Playground, you can wrap your existing code with a call to the runBlocking() function from the coroutines library. runBlocking() runs an event loop, which can handle multiple tasks at once by continuing each task where it left off when it's ready to be resumed.

- Move the existing contents of the

main()function into the body of therunBlocking {}call. The body ofrunBlocking{}is executed in a new coroutine.

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

delay(1000)

println("Sunny")

}

}

runBlocking() is synchronous; it will not return until all work within its lambda block is completed. That means it will wait for the work in the delay() call to complete (until one second elapses), and then continue with executing the Sunny print statement. Once all the work in the runBlocking() function is complete, the function returns, which ends the program.

- Run the program. Here's the output:

Weather forecast Sunny

The output is the same as before. The code is still synchronous - it runs in a straight line and only does one thing at a time. However, the difference now is that it runs over a longer period of time due to the delay.

The "co-" in coroutine means cooperative. The code cooperates to share the underlying event loop when it suspends to wait for something, which allows other work to be run in the meantime. (The "-routine" part in "coroutine" means a set of instructions like a function.) In the case of this example, the coroutine suspends when it reaches the delay() call. Other work can be done in that one second when the coroutine is suspended (even though in this program, there is no other work to do). Once the duration of the delay elapses, then the coroutine resumes execution and can proceed with printing Sunny to the output.

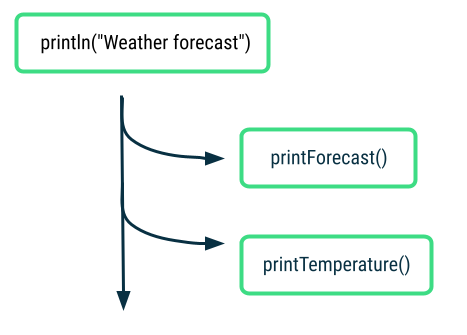

Suspending functions

If the actual logic to perform the network request to get the weather data becomes more complex, you may want to extract that logic out into its own function. Let's refactor the code to see its effect.

- Extract the code that simulates the network request for the weather data and move it into its own function called

printForecast(). CallprintForecast()from therunBlocking()code.

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

printForecast()

}

}

fun printForecast() {

delay(1000)

println("Sunny")

}

If you run the program now, you will see the same compile error you saw earlier. A suspend function can only be called from a coroutine or another suspend function, so define printForecast() as a suspend function.

- Add the

suspendmodifier just before thefunkeyword in theprintForecast()function declaration to make it a suspending function.

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

printForecast()

}

}

suspend fun printForecast() {

delay(1000)

println("Sunny")

}

Remember that delay() is a suspending function, and now you've made printForecast() a suspending function too.

A suspending function is like a regular function, but it can be suspended and resumed again later. To do this, suspend functions can only be called from other suspend functions that make this capability available.

A suspending function may contain zero or more suspension points. A suspension point is the place within the function where execution of the function can suspend. Once execution resumes, it picks up where it last left off in the code and proceeds with the rest of the function.

- Practice by adding another suspending function to your code, below the declaration of the

printForecast()function. Call this new suspending functionprintTemperature(). You can pretend that this does a network request to get the temperature data for the weather forecast.

Within the function, delay execution by 1000 milliseconds as well, and then print a temperature value to the output, such as 30 degrees Celsius. You can use the escape sequence "\u00b0" to print out the degree symbol, °.

suspend fun printTemperature() {

delay(1000)

println("30\u00b0C")

}

- Call the new

printTemperature()function from yourrunBlocking()code in themain()function. Here's the full code:

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

printForecast()

printTemperature()

}

}

suspend fun printForecast() {

delay(1000)

println("Sunny")

}

suspend fun printTemperature() {

delay(1000)

println("30\u00b0C")

}

- Run the program. The output should be:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C

In this code, the coroutine is first suspended with the delay in the printForecast() suspend function, and then resumes after that one-second delay. The Sunny text is printed to the output. The printForecast() function returns back to the caller.

Next the printTemperature() function gets called. That coroutine suspends when it reaches the delay() call, and then resumes one second later and finishes printing the temperature value to the output. printTemperature() function has completed all work and returns.

In the runBlocking() body, there are no further tasks to execute, so the runBlocking() function returns, and the program ends.

As mentioned earlier, runBlocking() is synchronous and each call in the body will be called sequentially. Note that a well-designed suspending function returns only once all work has been completed. As a result, these suspending functions run one after the other.

- (Optional) If you want to see how long it takes to execute this program with the delays, then you can wrap your code in a call to

measureTimeMillis()which will return the time it in milliseconds that it takes to run the block of code passed in. Add the import statement (import kotlin.system.*) to have access to this function. Print out the execution time and divide by1000.0to convert milliseconds to seconds.

import kotlin.system.*

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

val time = measureTimeMillis {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

printForecast()

printTemperature()

}

}

println("Execution time: ${time / 1000.0} seconds")

}

suspend fun printForecast() {

delay(1000)

println("Sunny")

}

suspend fun printTemperature() {

delay(1000)

println("30\u00b0C")

}

Output:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C Execution time: 2.128 seconds

The output shows that it took ~ 2.1 seconds to execute. (The precise execution time could be slightly different for you.) That seems reasonable because each of the suspending functions has a one-second delay.

So far, you've seen that the code in a coroutine is invoked sequentially by default. You have to be explicit if you want things to run concurrently, and you will learn how to do that in the next section. You will make use of the cooperative event loop to perform multiple tasks at the same time, which will speed up the execution time of the program.

3. Asynchronous code

launch()

Use the launch() function from the coroutines library to launch a new coroutine. To execute tasks concurrently, add multiple launch() functions to your code so that multiple coroutines can be in progress at the same time.

Coroutines in Kotlin follow a key concept called structured concurrency, where your code is sequential by default and cooperates with an underlying event loop, unless you explicitly ask for concurrent execution (e.g. using launch()). The assumption is that if you call a function, it should finish its work completely by the time it returns regardless of how many coroutines it may have used in its implementation details. Even if it fails with an exception, once the exception is thrown, there are no more pending tasks from the function. Hence, all work is finished once control flow returns from the function, whether it threw an exception or completed its work successfully.

- Start with your code from earlier steps. Use the

launch()function to move each call toprintForecast()andprintTemperature()respectively into their own coroutines.

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

launch {

printForecast()

}

launch {

printTemperature()

}

}

}

suspend fun printForecast() {

delay(1000)

println("Sunny")

}

suspend fun printTemperature() {

delay(1000)

println("30\u00b0C")

}

- Run the program. Here's the output:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C

The output is the same but you may have noticed that it is faster to run the program. Previously, you had to wait for the printForecast() suspend function to finish completely before moving onto the printTemperature() function. Now printForecast() and printTemperature() can run concurrently because they are in separate coroutines.

The call to launch { printForecast() } can return before all the work in printForecast() is completed. That is the beauty of coroutines. You can move onto the next launch() call to start the next coroutine. Similarly, the launch { printTemperature() } also returns even before all work is completed.

- (Optional) If you want to see how much faster the program is now, you could add the

measureTimeMillis()code to check the execution time.

import kotlin.system.*

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

val time = measureTimeMillis {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

launch {

printForecast()

}

launch {

printTemperature()

}

}

}

println("Execution time: ${time / 1000.0} seconds")

}

...

Output:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C Execution time: 1.122 seconds

You can see that the execution time has gone down from ~ 2.1 seconds to ~ 1.1 seconds, so it's faster to execute the program once you add concurrent operations! You can remove this time measurement code before moving onto the next steps.

What do you think happens if you add another print statement after the second launch() call, before the end of the runBlocking() code? Where would that message appear in the output?

- Modify the

runBlocking()code to add an additional print statement before the end of that block.

...

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

launch {

printForecast()

}

launch {

printTemperature()

}

println("Have a good day!")

}

}

...

- Run the program and here's the output:

Weather forecast Have a good day! Sunny 30°C

From this output, you can observe that after the two new coroutines are launched for printForecast() and printTemperature(), you can proceed with the next instruction which prints Have a good day!. This demonstrates the "fire and forget" nature of launch(). You fire off a new coroutine with launch(), and don't have to worry about when its work is finished.

Later the coroutines will complete their work, and print the remaining output statements. Once all the work (including all coroutines) in the body of the runBlocking() call have been completed, then runBlocking() returns and the program ends.

Now you've changed your synchronous code into asynchronous code. When an asynchronous function returns, the task may not be finished yet. This is what you saw in the case of launch(). The function returned, but its work was not completed yet. By using launch(), multiple tasks can run concurrently in your code, which is a powerful capability to use in the Android apps you develop.

async()

In the real world, you won't know how long the network requests for forecast and temperature will take. If you want to display a unified weather report when both tasks are done, then the current approach with launch() isn't sufficient. That's where async() comes in.

Use the async() function from the coroutines library if you care about when the coroutine finishes and need a return value from it.

The async() function returns an object of type Deferred, which is like a promise that the result will be in there when it's ready. You can access the result on the Deferred object using await().

- First change your suspending functions to return a

Stringinstead of printing the forecast and temperature data. Update the function names fromprintForecast()andprintTemperature()togetForecast()andgetTemperature().

...

suspend fun getForecast(): String {

delay(1000)

return "Sunny"

}

suspend fun getTemperature(): String {

delay(1000)

return "30\u00b0C"

}

- Modify your

runBlocking()code so that it usesasync()instead oflaunch()for the two coroutines. Store the return value of eachasync()call in variables calledforecastandtemperature, which areDeferredobjects that hold a result of typeString. (Specifying the type is optional because of type inference in Kotlin, but it's included below so you can more clearly see what's being returned by theasync()calls.)

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

val forecast: Deferred<String> = async {

getForecast()

}

val temperature: Deferred<String> = async {

getTemperature()

}

...

}

}

...

- Later in the coroutine, after the two

async()calls, you can access the result of those coroutines by callingawait()on theDeferredobjects. In this case, you can print the value of each coroutine usingforecast.await()andtemperature.await().

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

val forecast: Deferred<String> = async {

getForecast()

}

val temperature: Deferred<String> = async {

getTemperature()

}

println("${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}")

println("Have a good day!")

}

}

suspend fun getForecast(): String {

delay(1000)

return "Sunny"

}

suspend fun getTemperature(): String {

delay(1000)

return "30\u00b0C"

}

- Run the program and the output will be:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C Have a good day!

Neat! You created two coroutines that ran concurrently to get the forecast and temperature data. When they each completed, they returned a value. Then you combined the two return values into a single print statement: Sunny 30°C.

Parallel Decomposition

We can take this weather example a step further and see how coroutines can be useful in parallel decomposition of work. Parallel decomposition involves taking a problem and breaking it into smaller subtasks that can be solved in parallel. When the results of the subtasks are ready, you can combine them into a final result.

In your code, extract out the logic of the weather report from the body of runBlocking() into a single getWeatherReport() function that returns the combined string of Sunny 30°C.

- Define a new suspending function

getWeatherReport()in your code. - Set the function equal to the result of a call to the

coroutineScope{}function with an empty lambda block that will eventually contain logic for getting the weather report.

...

suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope {

}

...

coroutineScope{} creates a local scope for this weather report task. The coroutines launched within this scope are grouped together within this scope, which has implications for cancellation and exceptions that you'll learn about soon.

- Within the body of the

coroutineScope(), create two new coroutines usingasync()to fetch the forecast and temperature data, respectively. Create the weather report string by combining these results from the two coroutines. Do this by callingawait()on each of theDeferredobjects returned by theasync()calls. This ensures that each coroutine completes its work and returns its result, before we return from this function.

...

suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope {

val forecast = async { getForecast() }

val temperature = async { getTemperature() }

"${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}"

}

...

- Call this new

getWeatherReport()function fromrunBlocking(). Here's the full code:

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

println(getWeatherReport())

println("Have a good day!")

}

}

suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope {

val forecast = async { getForecast() }

val temperature = async { getTemperature() }

"${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}"

}

suspend fun getForecast(): String {

delay(1000)

return "Sunny"

}

suspend fun getTemperature(): String {

delay(1000)

return "30\u00b0C"

}

- Run the program and you see this output:

Weather forecast Sunny 30°C Have a good day!

The output is the same, but there are some noteworthy takeaways here. As mentioned earlier, coroutineScope() will only return once all its work, including any coroutines it launched, have completed. In this case, both coroutines getForecast() and getTemperature() need to finish and return their respective results. Then the Sunny text and 30°C are combined and returned from the scope. This weather report of Sunny 30°C gets printed to the output, and the caller can proceed to the last print statement of Have a good day!.

With coroutineScope(), even though the function is internally doing work concurrently, it appears to the caller as a synchronous operation because coroutineScope won't return until all work is done.

The key insight here for structured concurrency is that you can take multiple concurrent operations and put it into a single synchronous operation, where concurrency is an implementation detail. The only requirement on the calling code is to be in a suspend function or coroutine. Other than that, the structure of the calling code doesn't need to take into account the concurrency details.

4. Exceptions and cancellation

Now let's talk about some situations where an error may occur, or some work may be cancelled.

Introduction to exceptions

An exception is an unexpected event that happens during execution of your code. You should implement appropriate ways of handling these exceptions, to prevent your app from crashing and impacting the user experience negatively.

Here's an example of a program that terminates early with an exception. The program is intended to calculate the number of pizzas each person gets to eat, by dividing numberOfPizzas / numberOfPeople. Say you accidentally forget to set the value of the numberOfPeople to an actual value.

fun main() {

val numberOfPeople = 0

val numberOfPizzas = 20

println("Slices per person: ${numberOfPizzas / numberOfPeople}")

}

When you run the program, it will crash with an arithmetic exception because you can't divide a number by zero.

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ArithmeticException: / by zero at FileKt.main (File.kt:4) at FileKt.main (File.kt:-1) at jdk.internal.reflect.NativeMethodAccessorImpl.invoke0 (:-2)

This issue has a straightforward fix, where you can change the initial value of numberOfPeople to a non-zero number. However, as your code gets more complex, there are certain cases where you can't anticipate and prevent all exceptions from happening.

What happens when one of your coroutines fails with an exception? Modify the code from the weather program to find out.

Exceptions with coroutines

- Start with the weather program from the previous section.

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

println(getWeatherReport())

println("Have a good day!")

}

}

suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope {

val forecast = async { getForecast() }

val temperature = async { getTemperature() }

"${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}"

}

suspend fun getForecast(): String {

delay(1000)

return "Sunny"

}

suspend fun getTemperature(): String {

delay(1000)

return "30\u00b0C"

}

Within one of the suspending functions, intentionally throw an exception to see what the effect would be. This simulates that an unexpected error happened when fetching data from the server, which is plausible.

- In the

getTemperature()function, add a line of code that throws an exception. Write a throw expression using thethrowkeyword in Kotlin followed by a new instance of an exception which extends fromThrowable.

For example, you can throw an AssertionError and pass in a message string that describes the error in more detail: throw AssertionError("Temperature is invalid"). Throwing this exception stops further execution of the getTemperature() function.

...

suspend fun getTemperature(): String {

delay(500)

throw AssertionError("Temperature is invalid")

return "30\u00b0C"

}

You can also change the delay to 500 milliseconds for the getTemperature() method, so that you know the exception will occur before the other getForecast() function can complete its work.

- Run the program to see the result.

Weather forecast Exception in thread "main" java.lang.AssertionError: Temperature is invalid at FileKt.getTemperature (File.kt:24) at FileKt$getTemperature$1.invokeSuspend (File.kt:-1) at kotlin.coroutines.jvm.internal.BaseContinuationImpl.resumeWith (ContinuationImpl.kt:33)

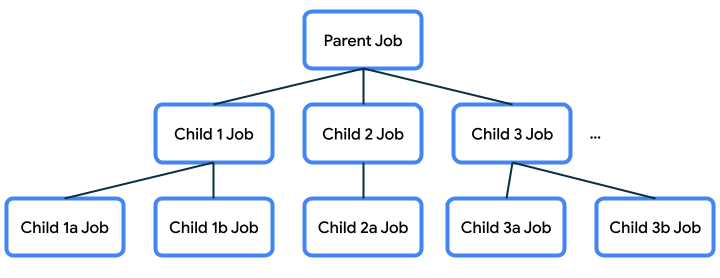

To understand this behavior, you'll need to know that there is a parent-child relationship among coroutines. You can launch a coroutine (known as the child) from another coroutine (parent). As you launch more coroutines from those coroutines, you can build up a whole hierarchy of coroutines.

The coroutine executing getTemperature() and the coroutine executing getForecast() are child coroutines of the same parent coroutine. The behavior you're seeing with exceptions in coroutines is due to structured concurrency. When one of the child coroutines fails with an exception, it gets propagated upwards. The parent coroutine is cancelled, which in turn cancels any other child coroutines (e.g. the coroutine running getForecast() in this case). Lastly, the error gets propagated upwards and the program crashes with the AssertionError.

Try-catch exceptions

If you know that certain parts of your code can possibly throw an exception, then you can surround that code with a try-catch block. You can catch the exception and handle it more gracefully in your app, such as by showing the user a helpful error message. Here's a code snippet of how it might look:

try {

// Some code that may throw an exception

} catch (e: IllegalArgumentException) {

// Handle exception

}

This approach also works for asynchronous code with coroutines. You can still use a try-catch expression to catch and handle exceptions in coroutines. The reason is because with structured concurrency, the sequential code is still synchronous code so the try-catch block will still work in the same expected way.

...

fun main() {

runBlocking {

...

try {

...

throw IllegalArgumentException("No city selected")

...

} catch (e: IllegalArgumentException) {

println("Caught exception $e")

// Handle error

}

}

}

...

To become more comfortable with handling exceptions, modify the weather program to catch the exception you added earlier and print the exception to the output.

- Within the

runBlocking()function, add a try-catch block around the code that callsgetWeatherReport(). Print out the error that is caught and also print out a message that the weather report is not available.

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

try {

println(getWeatherReport())

} catch (e: AssertionError) {

println("Caught exception in runBlocking(): $e")

println("Report unavailable at this time")

}

println("Have a good day!")

}

}

suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope {

val forecast = async { getForecast() }

val temperature = async { getTemperature() }

"${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}"

}

suspend fun getForecast(): String {

delay(1000)

return "Sunny"

}

suspend fun getTemperature(): String {

delay(500)

throw AssertionError("Temperature is invalid")

return "30\u00b0C"

}

- Run the program and now the error is handled gracefully, and the program can finish executing successfully.

Weather forecast Caught exception in runBlocking(): java.lang.AssertionError: Temperature is invalid Report unavailable at this time Have a good day!

From the output, you can observe that getTemperature() throws an exception. In the body of the runBlocking() function, you surround the println(getWeatherReport()) call in a try-catch block. You catch the type of exception that was expected (AssertionError in the case of this example). Then you print the exception to the output as "Caught exception" followed by the error message string. To handle the error, you let the user know that the weather report is not available with an additional println() statement: Report unavailable at this time.

Note that this behavior means that if there's a failure with getting the temperature, then there will be no weather report at all (even if a valid forecast was retrieved).

Depending on how you want your program to behave, there's an alternative way that you could have handled the exception in the weather program.

- Move the error handling so that the try-catch behavior actually happens within the coroutine launched by

async()to fetch the temperature. That way, the weather report can still print the forecast, even if the temperature failed. Here's the code:

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

println(getWeatherReport())

println("Have a good day!")

}

}

suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope {

val forecast = async { getForecast() }

val temperature = async {

try {

getTemperature()

} catch (e: AssertionError) {

println("Caught exception $e")

"{ No temperature found }"

}

}

"${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}"

}

suspend fun getForecast(): String {

delay(1000)

return "Sunny"

}

suspend fun getTemperature(): String {

delay(500)

throw AssertionError("Temperature is invalid")

return "30\u00b0C"

}

- Run the program.

Weather forecast

Caught exception java.lang.AssertionError: Temperature is invalid

Sunny { No temperature found }

Have a good day!

From the output, you can see that calling getTemperature() failed with an exception, but the code within async() was able to catch that exception and handle it gracefully by having the coroutine still return a String that says the temperature was not found. The weather report is still able to be printed, with a successful forecast of Sunny. The temperature is missing in the weather report, but in its place, there is a message explaining that the temperature was not found. This is a better user experience than the program crashing with the error.

A helpful way to think about this error handling approach is that async() is the producer when a coroutine is started with it. await() is the consumer because it's waiting to consume the result from the coroutine. The producer does the work and produces a result. The consumer consumes the result. If there's an exception in the producer, then the consumer will get that exception if it's not handled, and the coroutine will fail. However, if the producer is able to catch and handle the exception, then the consumer won't see that exception and will see a valid result.

Here's the getWeatherReport() code again for reference:

suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope {

val forecast = async { getForecast() }

val temperature = async {

try {

getTemperature()

} catch (e: AssertionError) {

println("Caught exception $e")

"{ No temperature found }"

}

}

"${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}"

}

In this case, the producer (async()) was able to catch and handle the exception and still return a String result of "{ No temperature found }". The consumer (await()) receives this String result and doesn't even need to know that an exception happened. This is another option to gracefully handle an exception that you expect could happen in your code.

Now you've learned that exceptions propagate upwards in the tree of coroutines, unless they are handled. It's also important to be careful when the exception propagates all the way to the root of the hierarchy, which could crash your whole app. Learn more details about exception handling in the Exceptions in coroutines blogpost and Coroutine exceptions handling article.

Cancellation

A similar topic to exceptions is cancellation of coroutines. This scenario is typically user-driven when an event has caused the app to cancel work that it had previously started.

For example, say that the user has selected a preference in the app that they no longer want to see temperature values in the app. They only want to know the weather forecast (e.g. Sunny), but not the exact temperature. Hence, cancel the coroutine that is currently getting the temperature data.

- First start with the initial code below (without cancellation).

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("Weather forecast")

println(getWeatherReport())

println("Have a good day!")

}

}

suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope {

val forecast = async { getForecast() }

val temperature = async { getTemperature() }

"${forecast.await()} ${temperature.await()}"

}

suspend fun getForecast(): String {

delay(1000)

return "Sunny"

}

suspend fun getTemperature(): String {

delay(1000)

return "30\u00b0C"

}

- After some delay, cancel the coroutine that was fetching the temperature information, so that your weather report only displays the forecast. Change the return value of the

coroutineScopeblock to only be the weather forecast string.

...

suspend fun getWeatherReport() = coroutineScope {

val forecast = async { getForecast() }

val temperature = async { getTemperature() }

delay(200)

temperature.cancel()

"${forecast.await()}"

}

...

- Run the program. Now the output is as follows. The weather report only consists of the weather forecast

Sunny, but not the temperature because that coroutine was cancelled.

Weather forecast Sunny Have a good day!

What you've learned here is that a coroutine can be cancelled, but it won't affect other coroutines in the same scope and the parent coroutine will not be cancelled.

In this section, you saw how cancellation and exceptions behave in coroutines and how that's tied to the coroutine hierarchy. Let's learn more of the formal concepts behind coroutines, so that you can understand how all the important pieces come together.

5. Coroutine concepts

When executing work asynchronously or concurrently, there are questions that you need to answer about how the work will be executed, how long the coroutine should exist for, what should happen if it gets cancelled or fails with an error, and more. Coroutines follow the principle of structured concurrency, which enforces you to answer these questions when you use coroutines in your code using a combination of mechanisms.

Job

When you launch a coroutine with the launch() function, it returns an instance of Job. The Job holds a handle, or reference, to the coroutine, so you can manage its lifecycle.

val job = launch { ... }

The job can be used to control the life cycle, or how long the coroutine lives for, such as cancelling the coroutine if you don't need the task anymore.

job.cancel()

With a job, you can check if it's active, cancelled, or completed. The job is completed if the coroutine and any coroutines that it launched have completed all of their work. Note that the coroutine could have completed due to a different reason, such as being cancelled, or failing with an exception, but the job is still considered completed at that point.

Jobs also keep track of the parent-child relationship among coroutines.

Job hierarchy

When a coroutine launches another coroutine, the job that returns from the new coroutine is called the child of the original parent job.

val job = launch {

...

val childJob = launch { ... }

...

}

These parent-child relationships form a job hierarchy, where each job can launch jobs, and so on.

This parent-child relationship is important because it will dictate certain behavior for the child and parent, and other children belonging to the same parent. You saw this behavior in the earlier examples with the weather program.

- If a parent job gets cancelled, then its child jobs also get cancelled.

- When a child job is canceled using

job.cancel(), it terminates, but it does not cancel its parent. - If a job fails with an exception, it cancels its parent with that exception. This is known as propagating the error upwards (to the parent, the parent's parent, and so on). .

CoroutineScope

Coroutines are typically launched into a CoroutineScope. This ensures that we don't have coroutines that are unmanaged and get lost, which could waste resources.

launch() and async() are extension functions on CoroutineScope. Call launch() or async() on the scope to create a new coroutine within that scope.

A CoroutineScope is tied to a lifecycle, which sets bounds on how long the coroutines within that scope will live. If a scope gets cancelled, then its job is cancelled, and the cancellation of that propagates to its child jobs. If a child job in the scope fails with an exception, then other child jobs get cancelled, the parent job gets cancelled, and the exception gets re-thrown to the caller.

CoroutineScope in Kotlin Playground

In this codelab, you used runBlocking() which provides a CoroutineScope for your program. You also learned how to use coroutineScope { } to create a new scope within the getWeatherReport() function.

CoroutineScope in Android apps

Android provides coroutine scope support in entities that have a well-defined lifecycle, such as Activity (lifecycleScope) and ViewModel (viewModelScope). Coroutines that are started within these scopes will adhere to the lifecycle of the corresponding entity, such as Activity or ViewModel.

For example, say you start a coroutine in an Activity with the provided coroutine scope called lifecycleScope. If the activity gets destroyed, then the lifecycleScope will get canceled and all its child coroutines will automatically get canceled too. You just need to decide if the coroutine following the lifecycle of the Activity is the behavior you want.

In the Race Tracker Android app you will be working on, you'll learn a way to scope your coroutines to the lifecycle of a composable.

Implementation Details of CoroutineScope

If you check the source code for how CoroutineScope.kt is implemented in the Kotlin coroutines library, you can see that CoroutineScope is declared as an interface and it contains a CoroutineContext as a variable.

The launch() and async() functions create a new child coroutine within that scope and the child also inherits the context from the scope. What is contained within the context? Let's discuss that next.

CoroutineContext

The CoroutineContext provides information about the context in which the coroutine will be running in. The CoroutineContext is essentially a map that stores elements where each element has a unique key. These are not required fields, but here are some examples of what may be contained in a context:

- name - name of the coroutine to uniquely identify it

- job - controls the lifecycle of the coroutine

- dispatcher - dispatches the work to the appropriate thread

- exception handler - handles exceptions thrown by the code executed in the coroutine

Each of the elements in a context can be appended together with the + operator. For example, one CoroutineContext could be defined as follows:

Job() + Dispatchers.Main + exceptionHandler

Because a name is not provided, the default coroutine name is used.

Within a coroutine, if you launch a new coroutine, the child coroutine will inherit the CoroutineContext from the parent coroutine, but replace the job specifically for the coroutine that just got created. You can also override any elements that were inherited from the parent context by passing in arguments to the launch() or async() functions for the parts of the context that you want to be different.

scope.launch(Dispatchers.Default) {

...

}

You can learn more about CoroutineContext and how the context gets inherited from the parent in this KotlinConf conference video talk.

You've seen the mention of dispatcher several times. Its role is to dispatch or assign the work to a thread. Let's discuss threads and dispatchers in more detail.

Dispatcher

Coroutines use dispatchers to determine the thread to use for its execution. A thread can be started, does some work (executes some code), and then terminates when there's no more work to be done.

When a user starts your app, the Android system creates a new process and a single thread of execution for your app, which is known as the main thread. The main thread handles many important operations for your app including Android system events, drawing the UI on the screen, handling user input events, and more. As a result, most of the code you write for your app will likely run on the main thread.

There are two terms to understand when it comes to the threading behavior of your code: blocking and non-blocking. A regular function blocks the calling thread until its work is completed. That means it does not yield the calling thread until the work is done, so no other work can be done in the meantime. Conversely, non-blocking code yields the calling thread until a certain condition is met, so you can do other work in the meantime. You can use an asynchronous function to perform non-blocking work because it returns before its work is completed.

In the case of Android apps, you should only call blocking code on the main thread if it will execute fairly quickly. The goal is to keep the main thread unblocked, so that it can execute work immediately if a new event is triggered. This main thread is the UI thread for your activities and is responsible for UI drawing and UI related events. When there's a change on the screen, the UI needs to be redrawn. For something like an animation on the screen, the UI needs to be redrawn frequently so that it appears like a smooth transition. If the main thread needs to execute a long-running block of work, then the screen won't update as frequently and the user will see an abrupt transition (known as "jank") or the app may hang or be slow to respond.

Hence we need to move any long-running work items off the main thread and handle it in a different thread. Your app starts off with a single main thread, but you can choose to create multiple threads to perform additional work. These additional threads can be referred to as worker threads. It's perfectly fine for a long-running task to block a worker thread for a long time, because in the meantime, the main thread is unblocked and can actively respond to the user.

There are some built-in dispatchers that Kotlin provides:

- Dispatchers.Main: Use this dispatcher to run a coroutine on the main Android thread. This dispatcher is used primarily for handling UI updates and interactions, and performing quick work.

- Dispatchers.IO: This dispatcher is optimized to perform disk or network I/O outside of the main thread. For example, read from or write to files, and execute any network operations.

- Dispatchers.Default: This is a default dispatcher used when calling

launch()andasync(), when no dispatcher is specified in their context. You can use this dispatcher to perform computationally-intensive work outside of the main thread. For example, processing a bitmap image file.

Try the following example in Kotlin Playground to better understand coroutine dispatchers.

- Replace any code you have in Kotlin Playground with the following code:

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

launch {

delay(1000)

println("10 results found.")

}

println("Loading...")

}

}

- Now wrap the contents of the launched coroutine with a call to

withContext()to change theCoroutineContextthat the coroutine is executed within, and specifically override the dispatcher. Switch to using theDispatchers.Default(instead ofDispatchers.Mainwhich is currently being used for the rest of the coroutine code in the program).

...

fun main() {

runBlocking {

launch {

withContext(Dispatchers.Default) {

delay(1000)

println("10 results found.")

}

}

println("Loading...")

}

}

Switching dispatchers is possible because withContext() is itself a suspending function. It executes the provided block of code using a new CoroutineContext. The new context comes from the context of the parent job (the outer launch() block), except it overrides the dispatcher used in the parent context with the one specified here: Dispatchers.Default. This is how we are able to go from executing work with Dispatchers.Main to using Dispatchers.Default.

- Run the program. The output should be:

Loading... 10 results found.

- Add print statements to see what thread you are on by calling

Thread.currentThread().name.

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

fun main() {

runBlocking {

println("${Thread.currentThread().name} - runBlocking function")

launch {

println("${Thread.currentThread().name} - launch function")

withContext(Dispatchers.Default) {

println("${Thread.currentThread().name} - withContext function")

delay(1000)

println("10 results found.")

}

println("${Thread.currentThread().name} - end of launch function")

}

println("Loading...")

}

}

- Run the program. The output should be:

main @coroutine#1 - runBlocking function Loading... main @coroutine#2 - launch function DefaultDispatcher-worker-1 @coroutine#2 - withContext function 10 results found. main @coroutine#2 - end of launch function

From this output, you can observe that most of the code is executed in coroutines on the main thread. However, for the portion of your code in the withContext(Dispatchers.Default) block, that is executed in a coroutine on a Default Dispatcher worker thread (which is not the main thread). Notice that after withContext() returns, the coroutine returns to running on the main thread (as evidenced by output statement: main @coroutine#2 - end of launch function). This example demonstrates that you can switch the dispatcher by modifying the context that is used for the coroutine.

If you have coroutines that were started on the main thread, and you want to move certain operations off the main thread, then you can use withContext to switch the dispatcher being used for that work. Choose appropriately from the available dispatchers: Main, Default, and IO depending on the type of operation it is. Then that work can be assigned to a thread (or group of threads called a thread pool) designated for that purpose. Coroutines can suspend themselves, and the dispatcher also influences how they resume.

Note that when working with popular libraries like Room and Retrofit (in this unit and the next one), you may not have to explicitly switch the dispatcher yourself if the library code already handles doing this work using an alternative coroutine dispatcher like Dispatchers.IO. In those cases, the suspend functions that those libraries reveal may already be main-safe and can be called from a coroutine running on the main thread. The library itself will handle switching the dispatcher to one that uses worker threads.

Now you've got a high-level overview of the important parts of coroutines and the role that CoroutineScope, CoroutineContext, CoroutineDispatcher, and Jobs play in shaping the lifecycle and behavior of a coroutine.

6. Conclusion

Great work on this challenging topic of coroutines! You have learned that coroutines are very useful because their execution can be suspended, freeing up the underlying thread to do other work, and then the coroutine can be resumed later. This allows you to run concurrent operations in your code.

Coroutine code in Kotlin follows the principle of structured concurrency. It is sequential by default, so you need to be explicit if you want concurrency (e.g. using launch() or async()). With structured concurrency, you can take multiple concurrent operations and put it into a single synchronous operation, where concurrency is an implementation detail. The only requirement on the calling code is to be in a suspend function or coroutine. Other than that, the structure of the calling code doesn't need to take into account the concurrency details. That makes your asynchronous code easier to read and reason about.

Structured concurrency keeps track of each of the launched coroutines in your app and ensures that they are not lost. Coroutines can have a hierarchy—tasks might launch subtasks, which in turn can launch subtasks. Jobs maintain the parent-child relationship among coroutines, and allow you to control the lifecycle of the coroutine.

Launch, completion, cancellation, and failure are four common operations in the coroutine's execution. To make it easier to maintain concurrent programs, structured concurrency defines principles that form the basis for how the common operations in the hierarchy are managed:

- Launch: Launch a coroutine into a scope that has a defined boundary on how long it lives for.

- Completion: The job is not complete until its child jobs are complete.

- Cancellation: This operation needs to propagate downward. When a coroutine is canceled, then the child coroutines need to also be canceled.

- Failure: This operation should propagate upward. When a coroutine throws an exception, then the parent will cancel all of its children, cancel itself, and propagate the exception up to its parent. This continues until the failure is caught and handled. It ensures that any errors in the code are properly reported and never lost.

Through hands-on practice with coroutines and understanding the concepts behind coroutines, you are now better equipped to write concurrent code in your Android app. By using coroutines for asynchronous programming, your code is simpler to read and reason about, more robust in situations of cancellations and exceptions, and delivers a more optimal and responsive experience for end users.

Summary

- Coroutines enable you to write long running code that runs concurrently without learning a new style of programming. The execution of a coroutine is sequential by design.

- Coroutines follow the principle of structured concurrency, which helps ensure that work is not lost and tied to a scope with a certain boundary on how long it lives. Your code is sequential by default and cooperates with an underlying event loop, unless you explicitly ask for concurrent execution (e.g. using

launch()orasync()). The assumption is that if you call a function, it should finish its work completely (unless it fails with an exception) by the time it returns regardless of how many coroutines it may have used in its implementation details. - The

suspendmodifier is used to mark a function whose execution can be suspended and resumed at a later point. - A

suspendfunction can be called only from another suspending function or from a coroutine. - You can start a new coroutine using the

launch()orasync()extension functions onCoroutineScope. - Jobs plays an important role to ensure structured concurrency by managing the lifecycle of coroutines and maintaining the parent-child relationship.

- A

CoroutineScopecontrols the lifetime of coroutines through its Job and enforces cancellation and other rules to its children and their children recursively. - A

CoroutineContextdefines the behavior of a coroutine, and can include references to a job and coroutine dispatcher. - Coroutines use a

CoroutineDispatcherto determine the threads to use for its execution.